Blood flows through the heart in one direction only. It is prevented from backing up by a series of valves at various openings: the tricuspid valve between the right atrium and right ventricle; the bicuspid, or mitral, valve between the left atrium and left ventricle; and the semilunar valves in the aorta and the pulmonary artery.

Each heartbeat, or cardiac cycle, is divided into two phases. In the first phase, a short period of ventricular contraction known as the systole, the tricuspid and mitral valves snap shut, producing the familiar "lub" sound heard in the physician's stethoscope. In the second phase, a slightly longer period of ventricular relaxation known as the diastole, the pulmonary and aortic valves close up, producing the characteristic "dub" sound. Both sides of the heart contract, empty, relax, and fill simultaneously; therefore, only one systole and one diastole are felt.

The normal heart has a rate of 72 beats per minute, but in infants the rate may be as high as 120 beats, and in children about 90 beats, per minute. Each heartbeat is stimulated by an electrical impulse that originates in a small strip of heart tissue known as the sinoatrial (S-A) node, or pacemaker.

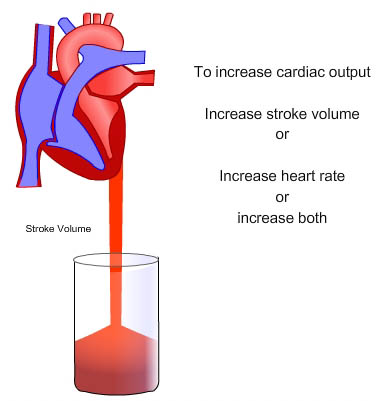

Cardiac output is the volume of blood being pumped by the heart in a minute. It is equal to the heart rate multiplied by the stroke volume. So if there are 70 beats per minute, and 70 ml blood is ejected with each beat of the heart, the cardiac output is 4900 ml/ minute. This value is typical for an average adult at rest, although cardiac output may reach up to 30 liters/ minute during extreme exercise.

So if there are 70 beats per minute, and 70 ml blood is ejected with each beat of the heart, the cardiac output is 4900 ml/ minute. This value is typical for an average adult at rest, although cardiac output may reach up to 30 liters/ minute during extreme exercise.

Factors affecting cardiac output in a healthy but untrained individual could be:

Heart rate can vary by a factor of approximately 3, between 60 and 180 beats per minute, whilst stroke volume can vary between 70 and 120 ml, a factor of only 1.5.

Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction/ Ejection Fraction The ejection fraction is a measurement of the heart's efficiency and can be used to estimate the function of the left ventricle, which pumps blood to the rest of the body. The left ventricle pumps only a fraction of the blood it contains. The ejection fraction is the amount of blood pumped divided by the amount of blood the ventricle contains. A normal ejection fraction is more than 55% of the blood volume. If the heart becomes enlarged, even if the amount of blood being pumped by the left ventricle remains the same, the relative fraction of blood being ejected decreases.

For example:

A reduced ejection fraction indicates that cardiomyopathy is present.

Stroke volume is the amount of blood pumped by the left ventricle of the heart in one contraction. The stroke volume is not all of the blood contained in the left ventricle. The heart does not pump all the blood out of the ventricle. Normally, only about two-thirds of the blood in the ventricle is put out with each beat.

What blood is actually pumped from the left ventricle is the stroke volume and it, together with the heart rate, determines the cardiac output, the output of blood by the heart per minute.

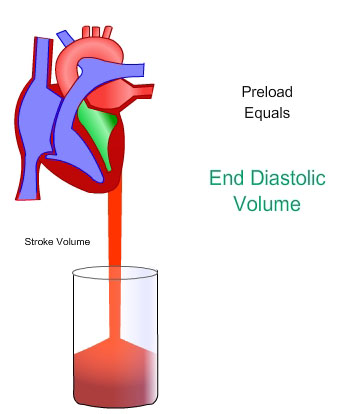

In cardiac physiology, preload is the volume of blood present in a ventricle of the heart, after passive filling and atrial contraction. If the chamber is not mentioned, it is usually assumed to be the left ventricle.

Preload is theoretically most accurately described as the initial stretching of cardiac myocytes prior to contraction. This cannot be measured in vivo and therefore other measurements are used as estimates. Estimation is inaccurate, for example in a chronically dilated ventricle new sarcomeres may have formed in the heart muscle allowing the relaxed ventricle to appear enlarged. Preload is affected by venous blood pressure and the rate of venous return. These are affected by venous tone and volume of circulating blood.

In cardiac physiology, afterload is the tension produced by a chamber of the heart in order to contract. If the chamber is not mentioned, it is usually assumed to be the left ventricle. Afterload can also be described as the pressure that the chamber of the heart has to generate in order to eject blood out of the chamber. In the case of the left ventricle, the afterload is a consequence of the blood pressure, since the pressure in the ventricle must be greater than the blood pressure in order to open the aortic valve.